『ネットワード・インターナショナル・サービス(以下、Netword)』会長、『パシフィック異文化教育アカデミー(以下、PCA)』学院長「ハロルド・A・ドレイク」がメディア掲載、取材等で取り上げられた記事を紹介致します。

以下、掲載記事

‘Stub’ sends a big message

Vol.48,No.100

April 11,1993

Pacific Sunday[Pacific Stars and Stripes]

By Hal Drake(Stripes Senior Writer)

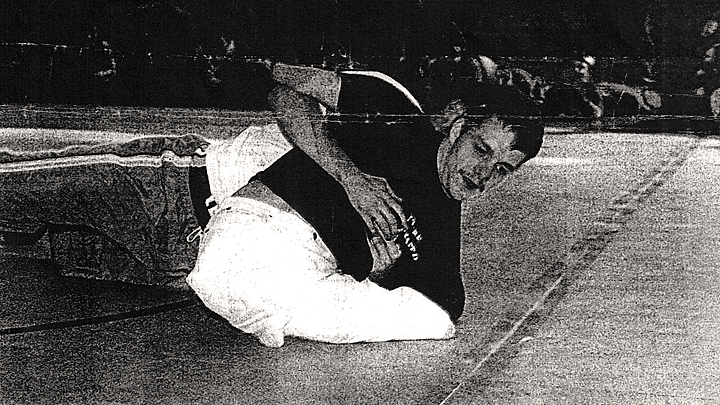

Spectators at Yokota High School watch in awe as ‘The Stub’ wrestles his opponent. Following the match, students line up to greet Brett Eastburn and Bill Essex. Brett says, “I do not think handicapped, therefore I am not handicapped.”

Brett Eastburn bristles at any suggestion that he is handicapped. If he could, Brett would collar anybody who said that set him straight. But he has no hands. He’d run a mile to prove his point, if he had been born with legs.

Brett came into the world limbless. He is no more than haunch high, mostly head and torso, traveling under an assumed name he pinned on himself — The Stub. Brett refuses to believe that, 21 years ago, he was thumbed out of life by an unfair referee.

At first an avoided figure who provokes pity or repulsion, Brett frequently finishes with young people around him, awed by a being who can do anything with nothing. He wasn’t awarded a handicap, Brett insists, but a solid and positive gift — the ability to work inspirational magic with others.

“Yeah, it really is, because I’ve seen time and time again, when I do everyday things in life,” Brett says, “people are impressed and use that as an example.”

he drives — easily pilots a van, putting stumps that end above the elbow into cups mounted on the wheel, working pedal and brake with special extensions. He feeds himself, skillfully grasping fork or glass with what little he has.

He’s an artist, holding brush or pencil between stub and shin. Several of his portraits and scenics have won important awards and nationwide recognition.

Brett wears his black felt and leather jacket from John Glenn High School in Walkerton, Ind., hung with medals and pendants — copper and bronze, close to gold. He was fourth in the 1988 AAU freestyle wrestling tournament, two slots away from a berth on the U.S. Olympic team.

“The Olympics,” Brett says. “Not the Special Olympics.”

Brett tells all that there are no handicaps, except those that people inflict on themselves — particularly the ones who fall to the worst infirmity. Drugs.

To get that across, Brett travels with an improbable partner. Bill Essex, a former Marine and retired detective, still has long hair and beard — the raffish deceiving many drug dealers who forfeited years of their lives. As an anti-drug troupe, they speak on campuses all over the United States, recently traveling overseas to talk to high school students at Yokota Air Base in western Tokyo.

Don’t do drugs, Essex said. It can mean personal ruin and prison sentence. Lay off illegal mind benders, Brett warned. They destroy physique and coordination,demolishing any natural athletic gifts.

Look at him, Brett says. All he can do with his drug-free body. He’ll wrestle anybody, he tells students at the school gym, to back what he says.

“I do not think handicapped, therefore I am not handicapped,” says Brett, seated atop a table next to the wrestling mat. “You are a success. You are a failure if you think you are going to be a failure.”

Drugs, he said, are built-in failure.

He told of the tough, grapple-and-pin world of amateur wrestling, particularly among those fighting for Olympic space. “They’re not going to take it easy on a little crippled dude.” Brett looked around the gym and challenged anybody to match or surpass him.

“I know you can do it. You can be ranked. If I can do it like this, no hands or feet, what’s your excuse?”

A volunteer steps forward, 18-year-old welterweight Trey Maestas. Brett somersaults off the table and veritably sprints on his haunches to the center of the mat. Trey, scissored by those stumps, is quickly pinned.

“A trap and roll,” Brett says. “Gets ‘em everytime.”

Was it a legitimate pin and not a sympathetic fix?

“Here,” Brett replies thrusting the right stub at an inquiring stranger. “Push.”

It’s like trying to move a jammed lever.

Brett Eastburn, unbelievable, is for real.

掲載記事:【パシフィック・サンデー 1993.04.11】