『ネットワード・インターナショナル・サービス(以下、Netword)』会長、『パシフィック異文化教育アカデミー(以下、PCA)』学院長「ハロルド・A・ドレイク」がメディア掲載、取材等で取り上げられた記事を紹介致します。

以下、掲載記事

The Asahi Shimbun "Weekend Beat"

FACE FROM THE PAST

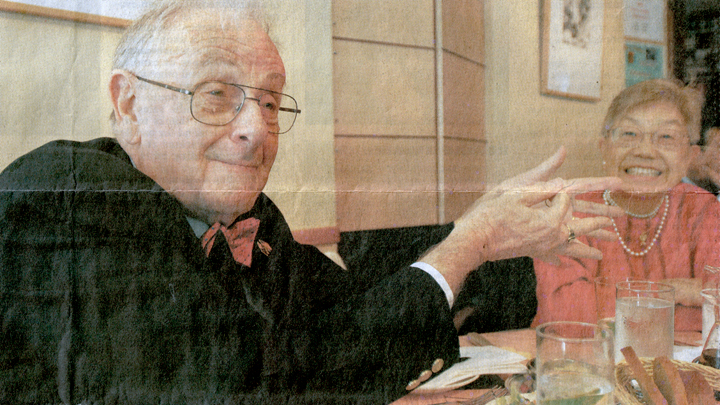

photo(Takahiro Yanai / Staff Photographer): Hal Drake, joined by his wife, Kazuko, talks about being a reporter for the Pacific Stars and Stripes at the Foreign Correspondents’Club of Japan in Tokyo.

When history ‘won’t let you alone’

"I remembered they had nice women there,oh boy, and so that was it."

HAL DRAKE(Journalist)

By JEREMEY LEMER

Contributing Writer

looking back over a life spent as a reporter in Japan, Hal Drake’s conversation skips from friends long dead to visions of war and reconstruction to the soldiers and sailors who have peopled his stories. Memories of face, noises and smells pour out in an urgent, tumbling stream, lubricated by a generous portion of gin and tons.

Now in his 70s, Drake was barely 26 when he first came to live in Tokyo in 1956 to work for the Pacific Stars and Stripes, the U.S. military’s unofficial newspaper. By then World War II had been over for more than a decade, and Japan, newly returned to self-rule, was beginning to shrug off year of U.S. administration.

Those were heady times for a young man from southern California, and Drake’s Japan was and will always be that of the postwar period, with its bombed-out cities and febrile reconstruction, the pulse of history beating in every corner and alley.

He recalls Japanese workers on U.S. Army bases were still stealing discarded food to feed family members and friends. Shinbashi was "wild and booming" and U.S. military personnel could still enjoy the "comforts" of the occupation — servants and private clubs.

Indeed, Drake didn’t come to Japan "to engage myself in culture and everything," he said mischievously. "I remembered they had nice women there,oh boy, and so that was it." His plans were short term, with no eye on a permanent career. He also didn’t plan to get married. "but it happened twice — one was disastrous and the other has worked out fairly well," he said, gesturing to his Japanese wife, Kazuko, who sat opposite him at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan in Tokyo.

In his articles, Drake probed beneath the dazzle of that era though, and his stories are haunted by the ghosts of the great conflict that destroyed and created in equal measure. Some ghosts were laid to rest, some were forgotten, but other wandered still. Like Teizo Morita, an admiral who headed the Japanese Imperial Navy’s Force Repair Department during the war, only to wind up a night watchman in an auto agency — "a baton of high rank" replaced by a "flashlight."

"This type of stuff, I kept running into," Drake said. "History just won’t let you alone."

And the past few months have proved his point. In August, several of his old articles were translated and republished in the Yomiuri Weekly, as part of look back at Japan’s postwar years. In September, he was interviewed about his recollections of Iwojima island by Yomiuri Shimbun in the run-up to the release of Clint Eastwood’s films about that epic battleground.

Still, the embrace with history is a mutual one. Despite retiring to Brisbane, Australia, in 1996, Drake was back in Tokyo in early December to talk to publishers about a collection of 25 of his best articles that he hopes to bring out in the near future. For the most part, they are profiles of men and women marked by World War II — a war Drake didn’t cover, but seems unable to forget.

"Young Japanese people don’t know the war," Kazuko Drake said, and she would like to change that by using Drake’s journalism to bring the era to life again. Drake, too, is determined to recover what he considers to be the lost voices of a significant period. "Many are vaults of stories seldom told or never told," he writes of his subjects in the introduction to his collected articles, "I couldn’t throw them in the back drawer of the past and slam it shut."

Drake cannot forget the past, but he can forgive. His published work shows a touching in sight into the process of reconciliation between former enemies, In one story, the brother of a U.S. pilot shot down in combat meets and pardons his brother’s killer, a Japanese fighter ace who renounced violence after the encounter and spent the war at the ministry of transportation. In another, Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force sailors and U.S. servicemen play softball on Iwojima, where so many of their compatriots died.

Such pieces might ring false from another reporter, but as a veteran of the Korean War, Drake knows what combat means. Drafted on March 5, 1951, he spent just over 10 months with an artillery regiment, during which time he had his share of traumatic experiences and close encounters.

One day he was stringing barbed wire on a hilltop. To cross a ditch, Drake threw his spool of wire and its canvas bag ahead of him. The bag rolled down the hill and exploded in a minefield. "You could see this piece of canvass" flapping around like a wounded bird," Drake said

And they had a point. Continually under censorship pressure from the military, even simple stories were vetoed dy Drake’s superiors.

In the 1960s, the Russians began a cultural charm offensive to win over the Japanese, flooding stages and campuses with attractions like the Bolshoi Ballet. "Stars and Stripes wasn’t allowed to print a paragraph about them. They were good shows, too," Drake said.

It took years to gain greater editorial independence. "I risked my job with staff revolts and everything to get it," Drake added. "Eventually we did… and by the time I left it was pretty good."

In spite of the restrictions, Drake put together some unique stories. In 1976, he wrote about the balloon bombs the Japanese manufactured out of wash paper during the 1940s as a way to take the war to U.S. soil.

The Japanese launched some 9,000 balloons packed with explosives in the hope that the winds would carry them across the Pacific where they would start forest fires and intimidate the population.

About 400 of the balloons, which were built by Japanese schoolgirls, made landfall. Most failed to detonate, and due to a media blackout by the U.S. government, it was only in the course of Drake’s reporting in 1976 that Kazuko Suai, one of the schoolgirl bomb makers, learned the consequences of their wartime handiwork — a mother and five children left dead in the forests of Oregon, the only U.S. domestic casualties of the war. The story later became the subject of articles by The New Yorker magazine and the British newspaper The Guardian.

Looking back, with the journalist’s instinctive sense of doubt, Drake is not sure what his millions of words have added up to. But moments of satisfaction do stand out.

In 1993, he wrote about Fumie Tanami, a 70-year-old widowed by the war. On a Sunday afternoon in 1941, she and her husband had planned to take in a movie, the James Stewart classic "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington." But conscription intervened; the outing was postponed and then canceled by a piece of shrapnel in China.

When Drake discovered that Tanami had never seen the movie, he sent her a copy. In a letter, she told Drake she had watched the movie with her husband’s photo by her side. "For once, for this old reporter writing stories… I felt good," Drake said.

掲載記事:【朝日新聞(Weekend Beat) 2007.01.20】